Having been constructed just as the city embarked on its ambitious project to lower the steep hill from 17th to 22nd along Dodge Street, El Beudor required a significant reconfiguration before opening its doors to its first tenants.

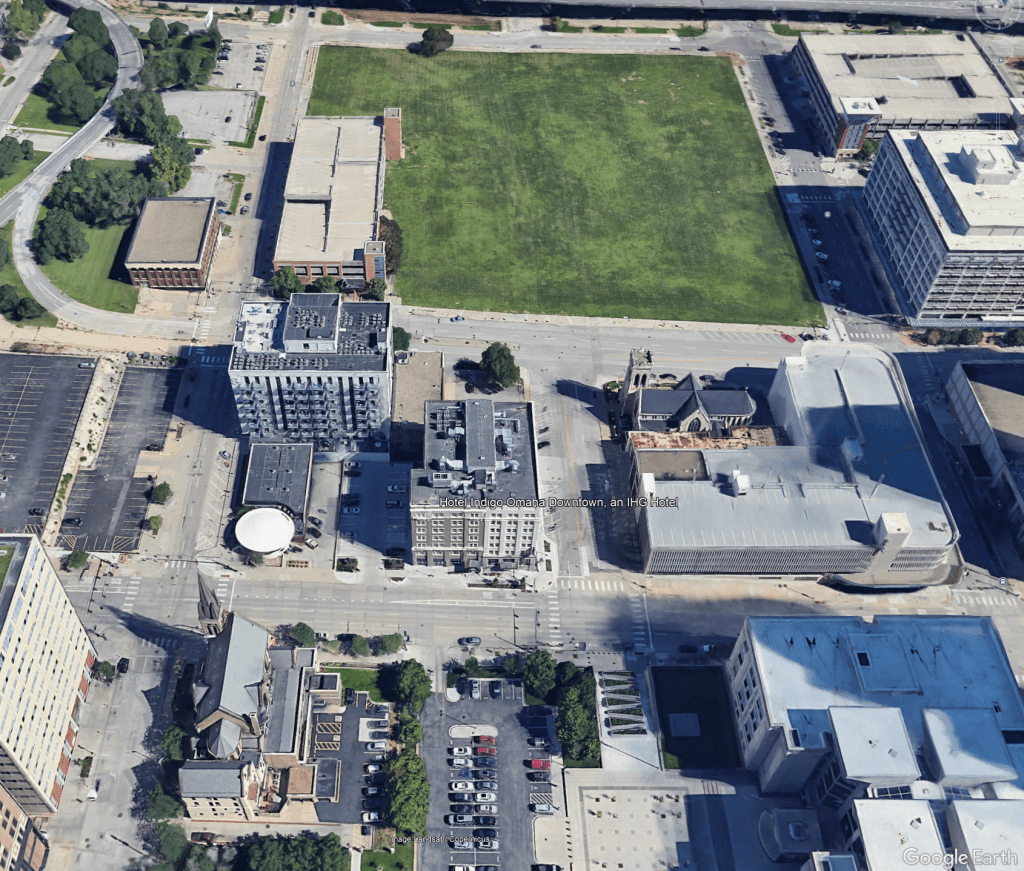

Located just west of the city’s historic red-light district, the building at 1804 Dodge Street was designed by architect James T. Allen. The U-shaped structure featured a terracotta and brick façade surrounding an open light court. Each side of the building was designed in such a way that it created the illusion of being two distinct buildings. Its construction was led by W. Boyd Jones, who opened Boyd Jones Construction a few years later.

The removal of 15 feet of dirt resulted in the original entrance and lobby ending up on what became the second floor. While the entrance was filled in with windows, the lobby was converted into a gathering space for tenants. In addition to adding a new entrance at the lower street level, four storefronts were created along 18th Street in an area that had previously been below grade.

El Beudor got its unusual name from the company’s secretary, Cassius Clay Shimer, who named it in honor of his three daughters—Elinore, Beula, and Dorothy—using the first syllable of each name. Home Builders Incorporated, the company that built the structure, moved its offices into the building and placed a large sign on the roof facing east toward downtown—an advertisement that was hard to miss.

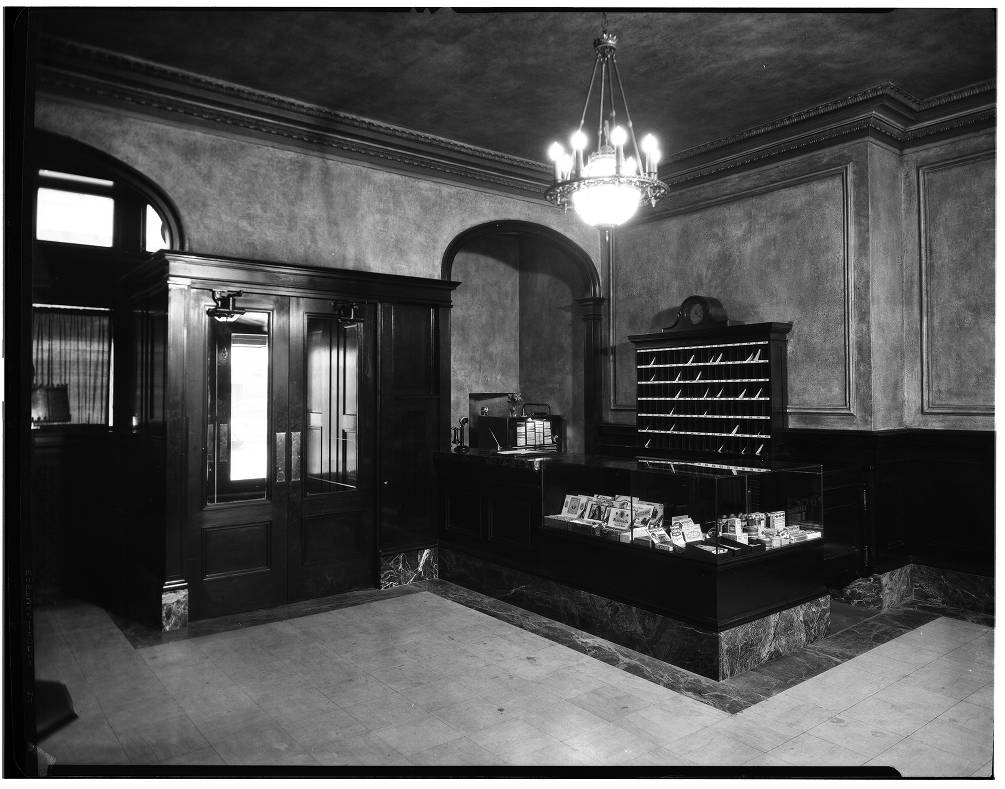

When it opened in 1919, El Beudor advertised itself as a luxury apartment building with hotel-like amenities. Inside the main entrance was a large lobby featuring marble floors, a grand staircase, and mahogany and walnut woodwork. With 110 units, it offered fully furnished rooms with private bathrooms, kitchenettes, and maid service. It also featured a service driveway that cut through the back of the east side of the building. Allowing cars to back in and unload items onto a loading dock with a freight elevator inside, tenants found it easy to transport belongings directly to their rooms. With apartments filled to capacity, the company continually raised rents while reducing amenities, leading to unwanted attention in the press.

Home Builders moved out of the building in 1926 ahead of its purchase by Eugene Eppley, owner of Eppley Hotels. After acquiring it at auction, Eppley renamed it Hotel Logan, after the Omaha chief and interpreter. He renovated the building, replaced many of its furnishings, and used the boilers in the basement to heat the nearby Hotel Fontenelle, which he also owned. Eppley Hotels moved its offices into the space once occupied by Home Builders. The company would go on to become the largest privately held hotel chain in the country, with 22 hotels spread across six states.

In 1956, the Sheraton Corporation bought the Eppley Hotel chain—including the Logan—in the second-largest hotel transaction in history at the time. It was a sign of things to come, as the building changed hands three more times over the following decades. It was acquired by Wellington Associates in 1968, American Savings in 1976, and Sylvester Properties in 1987. Like much of downtown, the hotel struggled as the city expanded westward.

Long removed from its days as a luxury apartment complex, the building continued its downward spiral before sitting vacant for several years starting around 2005—the same year it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

After multiple failed attempts to renovate and reopen the property, it was scheduled for demolition in 2016. As part of its preservation efforts, Restoration Exchange (now Preserve Omaha) “heart-bombed” the building in 2017. The attention helped, and in 2019 the property was acquired by Logan Hospitality. Lincoln-based contractor NGC Group completed a $21 million renovation, retaining several key historical elements, including the marble staircase.

Today, the building contains offices for NGC, top-floor condominiums, the 90-room Hotel Indigo, and Anna’s Place—the Anna Wilson-themed speakeasy. Rumors suggest the hotel’s basement once operated as a speakeasy during Prohibition, a past that the current hotel embraces as a key part of its story. It’s said that cement-filled cutouts in the basement may have been tunnels used to move alcohol throughout the city during the days when Tom Dennison’s machine ran Omaha. Perhaps the tunnels once used to heat the Fontenelle were originally used for this purpose? We may never know.

Content written by Omaha Exploration. If you enjoy my content, you can follow or subscribe on my Facebook page, signup to receive emails or make a donation on my website. Thank you and until next time, keep exploring!

Read my content on Grow Omaha: Local History by Omaha Exploration | Grow Omaha

Omaha Exploration is sponsored by @Rockbrook Mortgage Inc.

Click the logo to learn more

Click here to learn about opportunities to sponsor Omaha Exploration!

More pictures

Follow OE on social media!

Get an email when new content is posted

Omaha Exploration, 2025. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links can be used, if full and clear credit is given to Omaha Exploration with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Omaha Exploration proudly supports

Contact me or click the logo to learn more

Leave a comment